Recap #300: August Heat by W. F. Harvey

Title: August Heat by W. F. Harvey (1910)

Summary: Sometimes called a ghost story, sometimes just plain horror, two men, a criminal, and creation.

Initial Thoughts

Recap 300! I knew I wanted to recap something for such a momentous number (it has also been nine years to the month, if not the day, since Dove and I started this adventure with Dove’s recap of Funhouse by Diane Hoh! Recappers have come and gone, and I am grateful to every single one of them, and everyone who has commented/emailed/reached out, and everyone who has ever read a single recap. I’ll save the rest of my thanks for our big 10 year anniversary next January!), but almost all my time is going to family stuff and work right now. I needed something short, and I wanted something new.

Enter “August Heat” by W. F. Harvey. I’ve never read it, I’ve honestly never even heard of it much less read it, and here we go.

Recap

James Clarence Withencroft, a professional but not super successful artist, a man of 40 but perfectly healthy he is quick to tell us, has had a remarkable day and he simply must write all about it.

To whit: He ate, glanced through the morning paper, smoked his pipe, and randomly drew a criminal right after sentencing.

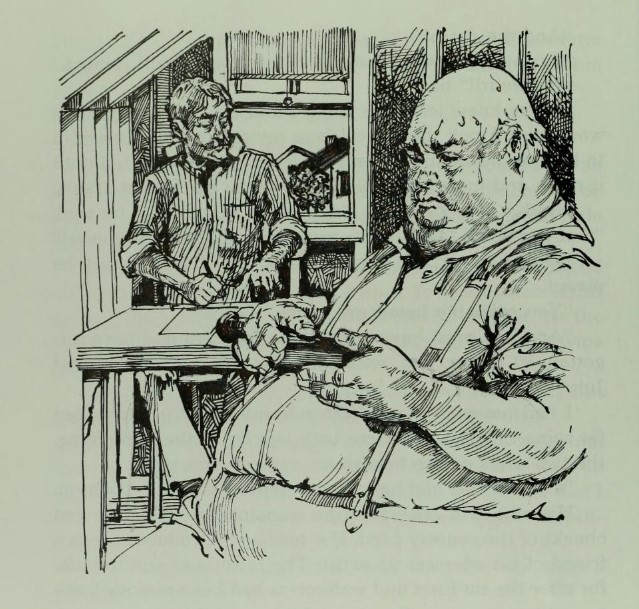

This criminal was, of course, “enormously fat” because what’s horror, even classic horror, without our old friend fat hate?

The flesh hung in rolls about his chin; it creased his huge, stumpy neck. […] He stood in the dock, his short, clumsy fingers clasping the rail, looking straight in front of him. The feeling that his expression conveyed was not so much one of horror as of utter, absolute collapse.

There seemed nothing in the man strong enough to sustain that mountain of flesh.

There’s this persistent idea, both in fiction and in reality, that fat people must be weak. Physically weak because of the shape of their bodies, but even more than that, emotionally weak, mentally weak, morally weak, because if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be fat. It is only weakness, badness, that leads to fatness. If they had willpower, if they were intelligent, if they were learned, they wouldn’t be fat. Good people, strong people, smart people, they aren’t fat.

Fat means you are a person of turpitude, moral, mental, emotional turpitude, you are wicked, depraved, immoral, corrupted. A fat person is a corruption of health, of goodness, of physicality, of what society wants to see in the world, of indulgence, of lack of self control, of a decaying world — I can go on, but I think you get my point.

The pushback against this is often that not all fat people are like that, not all fat people are unhealthy, not all fat people are lazy, not all fat people are weak, whatever, but here is the thing: fat people do not deserve to be treated as lesser, as bad, as weak just because they are fat. Doesn’t matter how or why or anything else.

…my rant is like half the length of this damn story. In short, there is nothing inherently bad about people just because they are fat, and I’d appreciate it if horror (if media, if reality) would back the fuck off when it comes to using fatness as a shorthand for evil.

Back to our dear Mister James Clarence Withencroft. He doesn’t know why he drew this man in particular, he doesn’t know why he rolls up the drawing to take with him. All of this is very, very convenient, mister.

He feels well pleased with his work and takes off for some purpose he’s also unsure of, and he ends up walking through the terrible heat ahead of the coming storm. He walks for miles, for hours, and ends up at a mason yard where a man works on a slab of “curiously veined marble.” Why curiously? Does it look like, oh, veins within skin perhaps?

Wait, who cares about curious marble, it’s the man from his drawing! “Huge and elephantine” and in the enormous flesh. Working with stone. Like he’s, you know, able to live a life while being fat.

(Don’t get me started on 300 pounds as the END OF THE WORLD weight that pops up in stories. You know, yeah, I’m fat, but at least I’m not that fat, god can you imagine being so fat you weigh 300 pounds, I’d just die. As if people at 300 pounds can’t live, and love, and fuck, and survive just like people at 100 pounds or 500 pounds or 250 pounds or whatever.)

(Okay, I’ll focus on the story.)

This version of the man is smiling, friendly, charming. He invites Withencroft to sit and rest, to take a break from the heat. They speak of the beautiful marble he’s working, and explains there’s a flaw on the back, though Withencroft himself probably wouldn’t notice. It’s fine in the heat, but when the winter comes, the cold will find the weak points in the stone.

It’s not for use in practice, though, in an actual graveyard, it’s a headstone for an exhibition, because just like artists, grocers, and butchers exhibit their wares, so too do headstone masons. (This is true. There’s a display down the street from the house where I grew up. Pretty and not as creepy as you might expect.)

Despite the lighthearted conversation, Withencroft feels uneasy; there’s “something unnatural, uncanny” in his meeting the man he drew. I love the combination of unnatural and uncanny there.

And it is a bit uncanny that he drew a man he then later met but had never seen before. The way Harvey allows the reader to connect the dots from Withencroft reading the paper right before he starts drawing to him drawing a criminal is a nice bit of letting the reader do the work, and that’s true no matter if the newspaper mentioned something that made him think of Atkinson or not.

Atkinson finishes his exhibit headstone and he puts Withencroft’s name and birthday on it, along with a death day of this day. Withencroft is, of course, perturbed to see that; Atkinson says that he put down the first name that he thought of even though he didn’t see it anywhere.

Withencroft then tells Atkinson about his own work that day, shows the drawing to him, and Atkinson too is disturbed; his friendly, engaging expression starts to look more like the drawing, which was a state of utter collapse, not surprise or horror.

“And it was only the day before yesterday,” [Atkinson] said, “that I told Maria there were no such things as ghosts!”

Neither of us had seen a ghost, but [Withencroft] knew what he meant.

No wonder this story is sometimes included in ghost story collections.

They talk back and forth over whether Atkinson heard Withencroft’s name somewhere or whether Withencroft saw Atkinson at Clacton-on-Sea last July, but he’d never been there in his life.

(I love place names like Clacton-on-Sea.)

Atkinson invites Withencroft in for dinner, they eat and Withencroft looks at art with Atkinson’s wife (I assume the above Maria), and then the men resume their conversation outside.

Atkinson can’t think of anything he’s done that would put him on trial. He turns talk to his flowers after that; he waters them twice a day in hot weather and sometimes the heat gets to the delicate ones anyway, especially the ferns.

In another quick conversational twist, he asks for Withencroft’s address, and Withincroft gives it. Despite all the wandering, Withencroft is only an hour from his home at a quick walk.

Atkinson decides they need to look at the matter directly. Withencroft needs to be careful if he goes home that night, avoid accidents, a cart running him over, ladders falling over him, slipping on banana skins or orange peels.

A few hours ago, his intensity and seriousness would have made Withencroft laugh, but not now. Atkinson suggests that he remain until twelve o’clock when the date of death would have passed.

They sit up in the a room under the eaves, hoping it will be slightly cooler inside, and smoke cigars while Atkinson sharpens some tools on a little oilstone. Withencroft writes at a shaky little table by the open windows. The leg is cracked, but Atkinson, a handy man, will mend it as soon as he finishes putting an edge on his chisel. There’s less than an hour left before Withencroft can leave for home. That’s not much time at all.

But the air is charged with thunder, the storm has not yet broken, and the heat is too much, too stifling, too overwhelming — “enough to send a man mad.”

Final Thoughts

Harvey doesn’t have much space to build suspense, on which this story turns, but by the last bit, sitting in the isolated room, in the heat and the promise of thunder and the unbroken storm, Harvey has built it.

The heat works particularly well, the pressure of it, the way things change when it is terrible, things wilt, things die, plants, people, patience.

The part that doesn’t work for me is the repetition of how Withencroft doesn’t understand why he drew that person, why he took the drawing with him, why he stops to talk, why he stays for dinner, why he stays after dinner to smoke and wait to see if he can survive until midnight. I’m not sure why it didn’t work for me, exactly. Possibly the short length meant it felt more like a convenient way to get Withencroft where he needed to be rather than something deeply unsettling.

I really enjoyed this, though, despite going boom over the fat hate that appears so often in horror fiction. I like the ambiguity of the story, particularly the ending, and the way this had a deep southern US horror feel to it even though it’s clearly not that.

There have been some radio adaptations of it over the years. I’ll have to track one down, see how it’s performed.

“There’s this persistent idea, both in fiction and in reality, that fat people must be weak. Physically weak because of the shape of their bodies, but even more than that, emotionally weak, mentally weak, morally weak, because if they weren’t, they wouldn’t be fat. It is only weakness, badness, that leads to fatness. If they had willpower, if they were intelligent, if they were learned, they wouldn’t be fat. Good people, strong people, smart people, they aren’t fat.”

I’m 35, I’ve been fat most of my life. I am still trying so hard to stop myself from thinking this way about myself and other fat people…it’s sad how ingrained it is in society.

It really is ingrained into society, and it can be incredibly difficult to overcome that message when it is everywhere and so easy to internalize. I know I struggle with it sometimes, still, no matter how much I logically know it’s not something I should think.