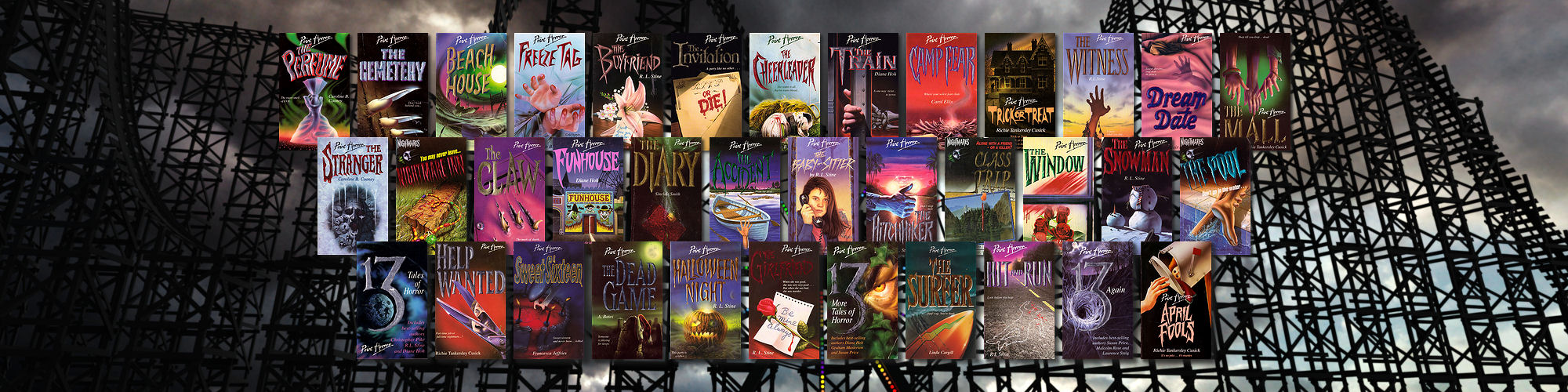

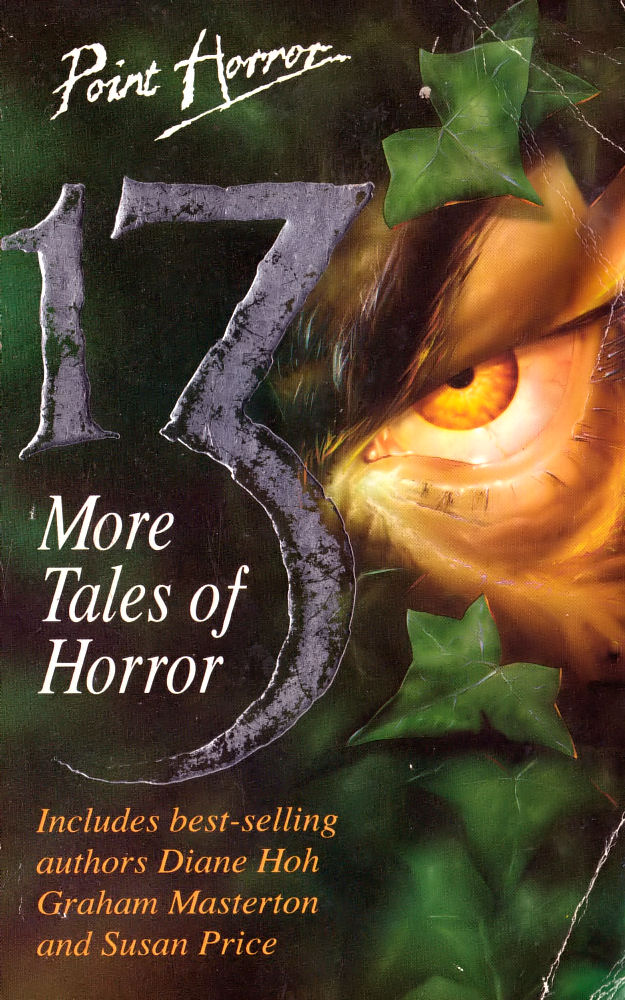

Recap #44: 13 More Tales of Horror Part Two

Title: 13 More Tales of Horror by Various

Summary: A terrifying journey into horror – thirteen tales guaranteed to fill you with fear. What are the mysterious creatures stalking the woods at night, and who will be their next prey? A chilling game of cat and mouse! Who is the mysterious party guest in the frighteningly real costume? Each breath he takes is death. Isn’t it lucky that the beautiful ring is so cheap? It’s all she wants for her birthday. Only this gift drives Kate out of her mind… Thirteen master storytellers invite you on a rollercoaster ride through the imagination. How much can you take?

Tagline: None

Note: As Dove requested, I’ve updated my template, because we now apparently call the Bad Guys Muffin Man. Hey, it makes as much sense as most Point Horrors.

Initial Thoughts:

I’ve read this one before, mostly because Dove threw it at me and told me I would love the first story, “The Cat-Dogs” by Susan Price. She was not wrong. I remember enjoying this collection a lot more than I did 13 Tales of Horror (Part One, Part Two, Part Three), but we’ll see if that is actually true. So far, it is true.

I will not be doing counters for the stories, because last time I find it annoying with short stories. I originally planned to do this in two parts, but I forgot how long each short story recap is, so instead we’ll break it into three parts. Go to part one.

Recap:

The House that Jack Built by Garry Kilworth

(Garry Kilworth is a sff and historical novelist, and has won or been shortlisted for some prestigious awards.)

You guys, this is the most British start to a story yet: Caleb Jones was lost on Bodmin Moor with only a few litres of petrol in the tank of his car.

Let me tell you how much hope I had for this story the first time I read it. MOORS. Night is coming. There’s probably a bright moon in the sky somewhere, behind the clouds. THERE SHOULD BE WEREWOLVES.

There are no werewolves. Woe.

Anyway, nearby is a large foursquare house. So I actually had to look this up because Wing is really fucking curious most of the time, but the only written explanation I could find was American four-square houses (though there are pictures of English four-square houses). Basically, a squared off house with mostly square rooms inside, though the American version generally has a porch the entire length of the front with two to three pillars holding it up. No word on whether the English version is the same. This particular house has simple lines but an imposing stature, and it looks like it had been dropped from the sky, because there is no garden or yard and the moor comes right up to its walls.

Yo, Dove! I thought garden = yard. Is there a difference? [Dove: The only time I’ve known a Brit to use “yard” to mean a space outdoors is sort of in a farm context. We had a garden that was ours, and the yard was a communal free-for-all, filled with the farm workers’ cars, tractors, and leading to the animal pens/fields, farm buildings. So did an American write this?]

Caleb stops the car and is overwhelmed by the silence. He doesn’t hear any animals, but he also doesn’t hear any wind, which is weird. The only thing is a stream that curves in and out of the moor, but it doesn’t seem to make much noise, either.

He’s pretty freaked out by the house; though it appears to be empty, it is in good repair with nothing neglected about it. There are no lights, and it looks eerie. Despite this, he has no real choice but to go see if anyone is there, because he’s not going to make it much farther before he’s in trouble. There’s no answer when he knocks on the door, and he is suddenly exhausted and actually takes a little nap on the porch.

[Dove: I’m thinking to all the houses I’ve seen with porches, and they tend to be a small cubicle around the front door. A small space to keep you dry while searching for your keys if it’s raining. I wish that English houses had the kind of porches seen in American architecture, but generally they don’t. So I’m wondering if this book was specifically meant to be set in England and Americans wrote stories set in England.]

He wakes the next morning, chilly and damp. This time, he actually tries the front door and finds it unlocked. Gee, you could have slept inside all this time. Rock on, Caleb. He goes inside and calls out to see if anyone is there. Surprisingly, there is a faint reply, and he’s embarrassed that he’s there so early. Before he figures out where the voice is coming from, the door slams shut behind him. He tries to open it, but there is no handle on the inside.

He follows the voice into a room off the hallway that has a glassless but barred window and beautiful walls decorated in wonderful carvings. There’s no ceiling, just red beams and a shiplap roof above, and the beams are carved with “primitive” villages, temples, and longhouses. Of course the “primitive” decorations have to be Polynesian or Indonesian.

(Also, what the hell is a shiplap roof? Apparently, it is what was used before plywood became widely available and can be a problem with asphalt shingles these days, but that doesn’t really tell me what it is, roofing companies.)

There’s no person in the room, and no furniture. When Caleb tries to leave, the door to the room slams shut. This door, too, has no handle, and he cannot prise it open. The wooden bars on the window are too strong to loosen.

As he’s messing with the window, the voice returns, telling him to leave it alone. It then tells him to put his hand through the hole. UMMMMM. CALEB. DO NOT DO THIS. [Dove: You’d be surprised how many times this nets positive results when you’re playing Silent Hill though.]

There is a knothole, as big as a fist, on an internal wall. He thinks maybe there is a key or a lever to release the door.

CALEB, I THINK YOU ARE ABOUT TO LOSE THAT HAND.

Sure enough, he puts his hand into the hole and it closes around his wrist. He tries to get free, but only hurts himself, and the voice tells him to stay still and feel the wall vibrate, because that is its voice. There’s some vibrations that are too loud, Caleb whines that he must be going crazy, the house sighs because that’s always the human answer to anything unusual. The house and I are in agreement here, though I think for different reasons.

The house tells Caleb that he is its prisoner and would remain so until he died; the house is immobile and can’t take care of itself, so it traps humans to do so. Damn, house, little needy, aren’t you?

Caleb tries to trick the house by agreeing with it and asking to get his tools out of the boot of his car. The house lets him out, but before he can get the car out of the way, the house throws a veranda post at him; it smashes the engine and enters the inside of the cab through the dashboard, ripping and tearing wires. The jagged end stops half a centimetre away from his chest. Way to go, Caleb.

Caleb realises that he is trapped, because the house could kill him before he ran. His first job is to repair the veranda, which is some shit, house. [Dove: Abuse ahoy! You made me hurt my knuckles when I punched you. Fix them.] There is a stack of seasoned wood in the lean-to, and he will also prepare more lumber from the copse of wood. He can only cut down mature trees, and has to do it with sympathy and understanding. He can’t cut down the fruit bushes and trees because he’ll need to eat them later or die. House, you might want to make sure he has more food than that, since you need him. If he dies, he’s of no use to you.

The house doesn’t approve of Caleb’s work at first, but in time, Caleb begins to appreciate the work he’s doing, because the house has been built to exacting standards, and the work is really lovely. He starts petting the house at random times. Well, Caleb, there is that knothole, if you’re not worried about maybe losing your dick…. [Dove: Wow, Wing. Just wow.]

Four of the eight bedrooms are filled with human provisions, so there is food beyond just fruit, and part of the copse has apples, pears, and plums, and there are gooseberry and blackcurrant bushes. There’s also a vegetable patch. No lie, this sounds like a pretty great place to live. Complete solitude, working with your hands, not having to worry about running out of food — I’m down. If you let me bring my dog and my books, I will happily stay forever. [Dove: This story always makes me think of Mr Wing. I think we even talked about it very early on in our friendship.]

There’s only one locked cupboard, and curiosity eats away at Caleb. When he tries to open it, the house asks why, and when he explains, it opens the cupboard. SHOCKINGLY, there is a human skeleton inside. It was the previous person the house captured, a hiker crossing the moor. Apparently, he died too soon and the house gave him a grave in one of its many pockets, which is creepy as shit. Caleb asks “too soon for what,” but the house doesn’t answer.

This inspires Caleb to try to run away the next time he works in the vegetable patch. The house catches him with a long white root. Spoiler: the house has roots, like a tree, and that is what holds it fast to the earth. So creepy. He’s punished by being locked in a room without food or water for two days.

In time, Caleb admits that it’s not a terrible situation. He’s very fit and well from all the work, and he had no ties to the outside world anyway, because his parents are dead and his girlfriend left him.

When he asks who made the house, it says that something made him, something without a name that is almost human. THAT IS FUCKING CREEPY AS SHIT. Caleb’s mind goes the same place mine did, which is to ask whether the house is a trap that catches people for this almost human thing. No answer. The house does admit that it is afraid of fire.

Caleb makes a joke that the almost human thing should be called Jack, and then has to explain the story of the House that Jack Built. The house likes hearing stories about houses, and Caleb tells him about the Three Little Pigs, Hansel and Gretel, the Little House on the Prairie, and some others. While he’s telling stories, he thinks about how humans regard houses as living things, sometimes worship them, care for them like pets.

This — is not something I’ve really considered before, and maybe explains a lot about why I’ve never felt the urge to buy a house. I don’t treat places I live like that. Maybe some of my things, but not the place itself. I’ve never been so tied to a place that I’ve wanted to stay, and that includes a physical home. (I also don’t decorate much on my own. My siblings do that for me, because I will live with blank walls and barebones furniture.) [Dove: You may think that Wing is exaggerating, but no. It only occurred to her to buy a couch when she got a dog because she wanted a place for the dog to sit. Until then, every skype conversation had taken place with Wing sitting on a cushion on the floor. For about a year.]

Caleb works for two years, always looking for a chance to escape. It’s super cold in the winter, which means I am noping out of this situation. NEVER MIND, HOUSE. WE COULD HAVE HAD IT ALL, BUT YOU DON’T BELIEVE IN LOTS OF WARMTH.

He finally comes up with a plan to escape. When he works in the vegetable garden or picks fruit, he slowly diverts the stream by dropping a single stone at a time into it, and as the water flows away from the house, the house becomes more and more lethargic.

The house asks why it’s so tired all the time, and Caleb is honest about the trickle of water and how it’s not getting enough water. It demands that Caleb fetch it more water, but Caleb points out he can’t bring something that’s not there, and it will have to get enough when it rains. It rains that night, and nothing more is said.

However a month later, there is a drought, and Caleb offers to see if there’s something out on the moor blocking the stream. Caleb goes out all chill, until he is beyond the reach of the roots. He follows the dry course of the stream, until the house tells him he shouldn’t go any further, and then he runs. He’s very fit and strong, and the house is weak and its aim is off, so he is fast enough to get away. Once he is out of range, he shouts that he beat it at last and he hopes it dries up and rots.

He then finds the nearest road and walks to the nearest town. AND THIS IS WHERE THE GODDAMN STORY SHOULD END, BUT NOPE, CALEB IS AN IDIOT.

And he doesn’t even go back to be a hero, which some people might be tempted to do. (To be honest, I might be tempted to go back to destroy it, because if I know something is dangerous, I need to fix it.)

Caleb, however, gets mad because the people at the pub don’t believe his story, and he wants to prove himself true. OH MY GOD, CALEB, YOU ARE AN IDIOT. I hope the house eats you.

He says they have to take weapons (petrol and matches) so the house can’t kill them, but he is going to go back. I DON’T THINK IT CAN BE SAID ENOUGH HOW HORRIBLE A PLAN THIS IS.

Caleb refuses to approach the house, but the men walk up and then back to the car and say that there is nothing but an empty old shack. Caleb finally walks closer, and it does look empty and hollow, a husk with no life. He tells himself that the house has died, probably through lack of water. Or maybe through lack of care, but now you are back, you ridiculous man.

SHOCKINGLY, the men drive off and leave him there. Caleb starts to run after them, but they are gone before he gets close. He then wonders, again, if the house is worth money, and now that is just dead wood, maybe he can sell it on the open market.

MORAL OF THE STORY: DON’T BE BOASTFUL AND GREEDY.

Caleb. Goes inside. The house. CALEB. GOES. BACK. INTO. THE. HOUSE. OH MY FUCKING GOD, CALEB, WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU DOING?!

The house feels dead, until he hears a faint creak. He convinces himself that even dead houses make noises, and then out the window he sees something glistening silver in the moon’s brightness. (SEE? WEREWOLVES.) The stream is back on its old course, and he doesn’t know who took away his dam. His instincts are telling him to run, but his legs won’t move. Something shuffles toward him, something the colour of an old root, something not very tall, not very smooth, not very human. It demands to know what Caleb did to its house, and Caleb finally runs.

Final Thoughts:

The story ends there, but I choose to believe he doesn’t survive, because returning to that house was RIDICULOUS.

CALEB. SERIOUSLY.

[Dove: I really like this story. For some reason, I find it sweet when the house realises it likes stories about houses (representation, yo). Caleb is an idiot. He really should have just counted his blessings he got away, and if the story needed a boo-scare at the end, have another moron get stranded near the house.]

The Station with No Name by Colin Greenland

(Colin Greenland is a sff author whose first short story won awards. He is also good friends with Neil Gaiman. This does not endear him to me.)

The station with no name exists, but nothing stops there anymore. There’s hardly enough light to see, and only a mucky, grudging, dark brown light filters down so that it looks like the bottom of the sea. (Pretty sure that’s more light than the actual bottom of the sea gets, but okay.) Every time your train passes through (I sincerely hope this story doesn’t continue with second person), the same thing happens: you go over a bump in the track and the train wheels spark; in that instant, you can see the station lit up in harsh white light, the bare walls, locked gates, shrouds of dust that turn it into an abandoned tomb. (Actually, I think bodies are required for a tomb.)

[Dove: Given that the story mentions that you only go through this station if you’re going “under the river”, I think it’s a tube (underground) station. You go under the river in London (most likely) or Liverpool (probably other places too, but those are the ones that pop into mind), and both of these are underground lines. It would be nice of the story to tell us that though. Also, there are plenty of disused tube stations in London, most of which have been photographed by urban explorers, so this story taps into things I like.]

Mark and Kix didn’t even mean to be headed on a line through the station that night, but they jumped two trains to lose a guy that was chasing them. (Good to know the second person only lasts a few paragraphs, but switching points of view like that is weird.) They’ve been out tagging places along the tracks. Mark sees the station with no name in the sharp sparks from the wheels, and how it is a clean slate, no tags.

They get off the train at the next station, do some tagging, and then Kix has to go home. Mark goes off on his own, trying to find an entrance to the old station. Finally he finds a small, dusty brick building that has two old shops gutted and boarded up and a dark gap in between. There’s a plywood door over the gap, but there is a hole and Mark slips through it.

He explores the place inside using his lighter, though he can only hold it while lit for so long and then it gets too hot. He feels like an explorer breaking into a pyramid in Egypt, and he loves the yards and yards of bare space with no fleck of paint anywhere. He decides he will mark everything and then take Kix on the train and show it to him, so Kix will be surprised by the whole place being Mark’s.

There are two black holes where the escalators had been torn out, and a black iron spiral staircase. This is gorgeous and creepy. He uses his lighter only once on the stairs, and nothing shows through the gratings underfoot. There is no breeze in this shaft, and thick cobwebs trailed over his face. (I’M DONE.)

When he reaches the bottom, there is a high metal fence, and no handle on the gate. He can’t climb the rails, he can’t bend them; when he kicks them, there is a dull, metal thud and then a dry pattering sound that whispered like shuffling feet.

Mark goes to one of the escalator hole and tries to work one of the struts (a long strip of steel) free. He focuses so hard on it he doesn’t notice the eyes gathering around him until his skin starts to crawl. He’s surrounded by big, black rats, and they are not afraid of his fire or his stomping. [Dove: Has anyone read The Rats by James Herbert? No? Take my advice: run.] They go away, he returns to the strut, and the eyes return.

He snaps the strut free and shouts that he is the Name. He uses the strut to break the lock on the gate. Finally he is inside the station with no name, and he starts to mark the place: his initials on the doorposts to warm up. Then he goes to the big station sign and makes an M:

The M he made did not look like an M. If it looked like anything, it looked like a fat blue balloon with invisible rubber bands wrapped round it. It gleamed down at him from the tiles. It was very blue, like a streak of sky glimpsed through the roof of a cave.

…

The A was like a razor unfolding, hooked in the fat side of the M. The wide curves of the M and the wicked thin curves of the A looked good together like that. Mark did the R, propped against them. The flick up at the end of the R was neat and sweet.

Mark hears that small, whispering sound again. This time it sounds like crumpling paper. He knows it is not just the rats or settling dirt. For the first time, he feels completely alone, there in the darkness beneath the surface.

He’s working on the K (“with the fins that always made him think of combs, and then a slashing upstroke”), when a hoarse voice asks what he thinks he’s doing. He finds an old man standing behind him, with long white hair and a white beard that is also yellow and brown and matted with filth. Mark assumes he’s a wino, and is ashamed of the fear that almost made him mess up his work. They exchange some barbs, and the old man threatens to report him. He then says there will be no train until they clear the line, because the bombers got the line. The old man keeps making WWII references, and Mark heads off to do more marking — except there are more people. The second one is a young woman, thin and white as a fish in a headscarf and carpet slippers rotting on her feet. When she touches Mark’s arm, her hand is cold and damp as a lump of putty, and a wet, bad smell comes off her. She’s looking for her Betty.

A train comes down the tunnel, and Mark pulls her into the shadow of a pillar. The train is a track maintenance rig and goes past very slowly. The woman’s smell makes him sick while they stand together.

Once the train is gone, Mark goes back to marking things and more people show up. They talk at him creepily, he shouts and runs and crosses the tracks, and then goes into the waiting room, looking for more space to paint, and, of course, it is full of skeletons, slimy bones and hanks of hair and empty shoes, and they all stand up to welcome him.

Kix is riding in a cop car looking for Mark, but there’s no sign. He gets the train home, and that is when he sees Mark’s throw, his name all over the space. He does wonder why Mark changed his colour, though; he uses blue normally, but all the “marks” are red, bright and sticky looking, as if still wet.

Final Thoughts:

This is nicely creepy, though it feels like it takes forever to read. I particularly like the ending.

[Dove: Agreed, I love creepy abandoned places.]

Something to Read by Philip Pullman

(Philip Pullman is probably best known for the His Dark Materials trilogy, which is interesting, because he doesn’t actually like fantasy novels, and has spoken out in very disparaging ways about them.)

Annabel wanders down an unlit corridor toward the school library. She touches the wallpaper lightly as she walks; there’s a torn patch near the secretary’s door, and if she doesn’t properly skim over it without touching the bare plaster, she has to go back to the corner and start again, no matter how long it takes. I’m feeling some OCD for Annabel.

She can hear the school disco in the distance; it is nearly dark in her part of the school, and “the remains of the day were straining the sky red over the roofs of the houses on the estate; little solid clouds coloured like lemon, butter, and apricot floated even higher up, against a background of navy blue.”

She sees a group of boys surrounding a motorbike in the school gateway. She doesn’t recognise the one with the helmet, but the others are in her class. She opens the door to shout at them, and the boy with the helmet says something rude. She thinks boys like that should be punished, but nobody wants to do so.

The trophy cabinet nearby hasn’t been touched since 1973, nothing moved and no new names added. It’s a relic of the days when the school had been a grammar school. Annabel stares at her reflection for a bit, and her too short green dress. She’s been forced to come to the disco, and she doesn’t want to be there.

The library door is locked, and she is bitterly disappointed — and even more so when she sees the latest novel by Iris Murdoch on the new acquisitions shelf. She’s read all her other books, and sometimes feels as if Iris is writing for her. (This is one of the joys of being an author.)

Annabel is an obsessive reader (and compares it to a drug-addict needing a hit, which is a pretty shitty comparison), and she measures her life by what she’s reading at that time. She feels different from other people because she loves to read, which I think is a common feeling but is kind of ridiculous. If people didn’t buy books, books wouldn’t be published. Her parents have forced her to come to the disco because they think she needs to spend more time with other people her own age. Which is fair, but kind of sucky that she feels like they are desperate to make her change.

She finally makes her way to the disco, tries to talk to a teacher, and then the teacher goes off to dance with one of the students. Is that normal in England? [Dove: Nope. Then again, the only school disco I went to was at a friend’s school. But no, no teachers dancing with students.] A boy named Tim (very ordinary, slightly plump, didn’t read much) asks her to dance, and she asks “whatever for” because Annabel is kind of a dick. This embarrasses him, because of course it does. Poor guy.

Annabel remembers that she has left a book in her PE bag, which is hanging in the cloakroom. It’s not a novel, but a book about collecting and polishing semi-precious gemstones. She takes it out to the swimming pool, because surely no one would go there. (Except for people sneaking off to skinny dip and hook up, but maybe I’m expecting too much of these kids.)

The door to the pool is locked, but she doesn’t let that stop her, and she climbs over the wall awkwardly. The moon turns everything silver except for the shiny black water in the pool, and this is simultaneously creepy and gorgeous.

She’s just sitting down to read when, sure enough, Linda and Ian turn up, and Linda tells her to go somewhere else because they “was there first.” Annabel of course corrects them, because that is the type of person Annabel is.

Linda and Annabel argue a bit, and then Linda flings the book into the swimming pool. Annabel freaks out, tries to rescue it without getting into the pool, and then slaps Linda. She then tries to force Linda into the pool to rescue the book, but Annabel falls in instead. She’s not good at swimming, but she’s surprised that she sinks immediately, and can only blame her green dress, because human bodies tend to float.

She tries to get out, tries to get the book, can’t — and then realises that Ian and Linda are staring down at her, and she is dead. She gets out of the pool and watches her body float to the surface. Ian and Linda talk about what they should do, and then Ian sends Linda to find a teacher.

Annabel tries to talk to Ian about what he should do, but of course, he can’t hear her. Mr Carter shows up and drags her body out of the pool with Ian’s help. They take her into the building, call her parents, and Annabel thinks about how grotesque her body looks now that she’s dead. She leaves the room when her parents show up, and learns she can walk through walls. Of course she heads straight to the library, because she is not thinking this through. She’s excited to read the new Iris Murdoch book, but of course she can’t actually touch the book.

She then realises that she’ll never be able to read again unless she reads while someone else reads, but she won’t be able to choose her own books. She has all the books in the world and nothing to read.

Final Thoughts:

This is probably the most morality tale story in the book, and that’s saying something after Caleb’s story up there. I don’t like this one much, probably because it is a morality tale.

[Dove: I remember being terrified of the idea of not being able to read when I first read this. Although I did want to slap Annabel for being a dick. Loving books = good. Being a dick to other humans because they’re not books = not so good.]

Killing Time by Jill Bennett

(Jill Bennett writes mostly books for young kids and used to be a librarian.)

Note: There is animal death in this story.

Philip toils up a hill toward Crouch Wood carrying a dead rabbit; he has been ordered to kill, and though he is elated with it, he is also afraid. Inside the woods, he finds the caravan there still, and sitting on the wooden steps in front of it, the White Man. The White Man takes the rabbit; Philip stands frozen in front of him, and feels like the White Man can see into his very soul.

Now that Philip has killed, he is a part of them always, and the White Man gives him a shiny alarm clock. Once he winds it up, once it starts to tell time, they will always be his friends and will never leave him.

Philip takes it eagerly, but stops before he winds the key in the back. White Man gets impatient with him, and after he shouts, Philip starts the clock ticking. He thinks he will be important at home; there is only one other clock there, and so him having one is a big deal. The White Man tells him to wind the clock every day, and to make sure that no one else winds it; it will bring him back to them when he has to come.

Philip runs home. Once he’s out of the woods, figures come out of the caravan and stand in a circle with the White Man.

Nick is super hot and can’t sleep. No air comes through his open window. He tries to ignore the outside night noises, and instead listens to the ticking of the battered old-fashioned alarm clock. Its chromium case is blotched and roughened after all the years. Nick stole it that afternoon.

He first saw it when he was very young — younger than Sally is now, so maybe six — and he fell in love with it. His granddad kept it in the garden shed on a back shelf out of Nick’s reach. Nick spent years trying to get it, and every time he did, his granddad stopped him, shouting. Apparently, it belong to his granddad’s brother (Phil), and granddad has kept it in memory. His granddad never liked it, and always felt like it was watching them. Phil was thirteen when they lost him, but at first, he won’t tell Nick the rest of the story.

That was two years ago, and now Nick is thirteen, and his grandmother died, and granddad has been weird ever since. Sometimes he even calls Nick “Phil”, and Nick finds that very creepy. (It kind of is!)

Nick was helping granddad pile papers in the shed when he once again saw the alarm clock, and stole it. Finally, he falls back asleep, and dreams of the wind lashing the branches of the cherry tree against the window. Granddad hangs from the tree, a noose around his neck, and then his face turns into a young boy who has no pupils in his eyes.

Nick wakes at ten past six, per his stolen clock, but there is no sign of dawn. He falls asleep again, and then it is the next morning. His mother is pregnant, his father is on the early shift at the milk factory, and Sally, his little sister, is excited over the cat, Crissy, having five kittens. (Sally also has a flop-eared rabbit, Freddie, and I bet one of these pets ends up dead soon.)

Their mother sends them off to buy eggs and ice [Dove: they mean an ice cream or lolly. Around the 40s/50s, people used to refer to ice cream cones/lollies as “ices”. But by the 80s, it would have been “ice cream” or “lolly”. So this kind of makes no sense. I can see that phrase being used in the Phil timeline, but not “now”. Maybe the author was trying to be Enid Blyton.], and Nick asks Mrs Potts about Philip, because she went to school with his granddad. She says that Philip was a “rum ‘un” and Sally doesn’t know what that means. Me neither. [Dove: Unruly.] Nick suggests that means he got into trouble a lot. He doesn’t wait for her to answer, though, he just asks if Philip died young because of an accident. Eventually, she tells him to ask his granddad about it, and that it was bad and is best forgotten.

On the way home, Sally asks about the clock, and he turns on her viciously, threatening to kill her rabbit if she comes into his room. He takes off for Crouch Wood.

Next scene is Nick dreaming again. He’s holding one of the kittens in his hand, and he wants to squeeze it to death, but instead he puts it down — and then stomps on it.

He wakes up screaming, and his mother comes in to comfort him. He doesn’t tell her much about the dream, but she soothes him, and then tells him he can sleep on the patio on the sunbed, where it will be cooler.

We switch to Philip, who is wearing a white dress thing and standing in the woods on his bare feet, terrified and confused. A voice tells him, “Philip, willing and chosen, we salute you.”

The White Man comes out of the trees holding a knife out to Philip. A dog lies on the ground, helpless and drugged, and the White Man and the shadowy figures want him to kill it because the earth needs new blood. Philip can’t kill the dog, but the White Man tells him if he doesn’t kill the dog, it will have to be someone else.

Nick is woken up by rain, and returns to his room. He listens to the tick of the clock, and becomes obsessed, falls into sleep hearing only it. When he wakes the next morning, though he’s slept, he is not refreshed. Nick is very remote with his family, and nasty; he goes to look at the five kittens, then takes one of them, a tiny ginger kitten, and realises he’s back in his dream. He’s just about to put it down to stomp on it when Sally catches him. He wants to destroy everything, but instead gives the kitten to her and stomps off back to the woods.

Sally is worried about him, and why he’s spending so much time alone in the woods, and why he’s been so nasty to everyone — then granddad shows up. He talks about a summer when he was a boy that was just as hot as this one, and Sally tries to get him to talk about Philip. He does, a little, about how different they were, how Philip loved to be outdoors and granddad was a bit of a dreamer. Granddad feels like it is his fault, and if he’d just been more company for Philip, he wouldn’t have found those people. Philip thought the Albino, as the others called him, was wonderful, but everyone else was scared of him. They never found the Albino after, or any of the others — but before Sally can get an answer out of that, her mother comes in, because the baby is coming.

They have a boy, Peter, and Sally can’t wait to meet him. Nick gets worse and worse, and Sally sometimes follows him, being as quiet as possible. She finds him sitting in a clearing, listening to the ticking of the clock, which is always with him now. He can hear voices in the ticking, luring, beautiful voices that promise him wonderful things if he just does one thing for them first.

Nick goes to get a kitten, but finds Crissy and the kittens gone. He accuses Sally of moving them, and Sally says that Crissy has hidden them because she didn’t like him touching them. She refuses to tell him where they are, and he starts twisting her arm, trying to force her to tell him. Granddad wakes up and saves her, and Nick storms off because he has more than one string to his bow. Now that’s a phrase I haven’t heard in awhile.

Sally finally tells granddad about the clock, and he tells her to grab it. They check on Nick, who is still walking up the hill, and he’s taken Freddie, the rabbit, with him. Granddad hurries off after him, because this time he has to stop him. Sally races after them, but she’s too short to keep up.

Granddad finds Nick in the clearing; there are shadows, and in them he thinks he sees people. They surround Nick, and granddad tries to shout to save him, but can’t move. Nick takes out a kitchen knife and a length of washing line; he ties that into a noose and throws it over a branch. He then picks up the knife and starts to untie the second bag he’s carrying, which has the rabbit in it, of course. Amongst all the shadows, Granddad sees a white figure.

Sally arrives just in time to scream Freddie’s name; Nick throws the knife away from himself, or the white figure does, granddad can’t tell. He runs to Nick; Nick stumbles and falls. They’re alone in the woods after that, Nick, granddad, and Sally, who has her pet rabbit.

Sally rages at Nick, but granddad says it wasn’t Nick, it was old evil. He tells Sally about Philip, and how the Albino gave him the clock, and the day Philip died he got odder than ever. Before he headed up to the woods, he told granddad to come find him if he was there by six, but granddad forgot while he was reading, and the clock had stopped at ten past six. That was when Philip died too. Finally, granddad smashes the clock, which he says he should have done decades ago.

Granddad sends Sally to see if her dad is back, because they will need his help to get Nick down the hill. He thinks back to how terrible it was when he found Philip hanging from a tree with the dead dog at his feet.

Nick wakes up, and granddad helps him down the hill. Everything is going to be fine, now, apparently.

Final Thoughts:

This is creepy enough, but the pacing is weird, and the ending is a let down. Not that they all survive, but it just feels flat.

[Dove: Agreed, it felt like it was building up to something, and then it’s like, “Nah, we’re good. Let’s just throw the brakes on abruptly.”]

Thank you!

When my friend gave me the book she told me I was just like Annabel. I think I’m less of a dick, although I would have read at teenage parties if I could have got away with it.

So, did your friend ever try to push you into a pool?

I empathise with Annabel so much, from the reading, to being forced to attend school events, to not wanting to be around other people at all. Except that I would never have been rude to anyone; to this day I am mortified by the idea of hurting someone’s feelings. I do correct poor grammar though.

I’m now waiting for a sequel in which the library is terrorised by a poltergeist until someone figures out that leaving audiobooks playing 24/7 keeps it (her) calm and content.

Ha! Not that I recall. 🙂